When One Tin Soldier Rides Away

My first childhood hero was an agent on the popular television program, “The FBI.” Despite getting shot every week or two, he never complained and always managed to get the bad guy. Alas, a tour of FBI headquarters did to my hero-agent what all those bullets couldn’t: killed him off when I learned he was nothing more than a Hollywood actor.

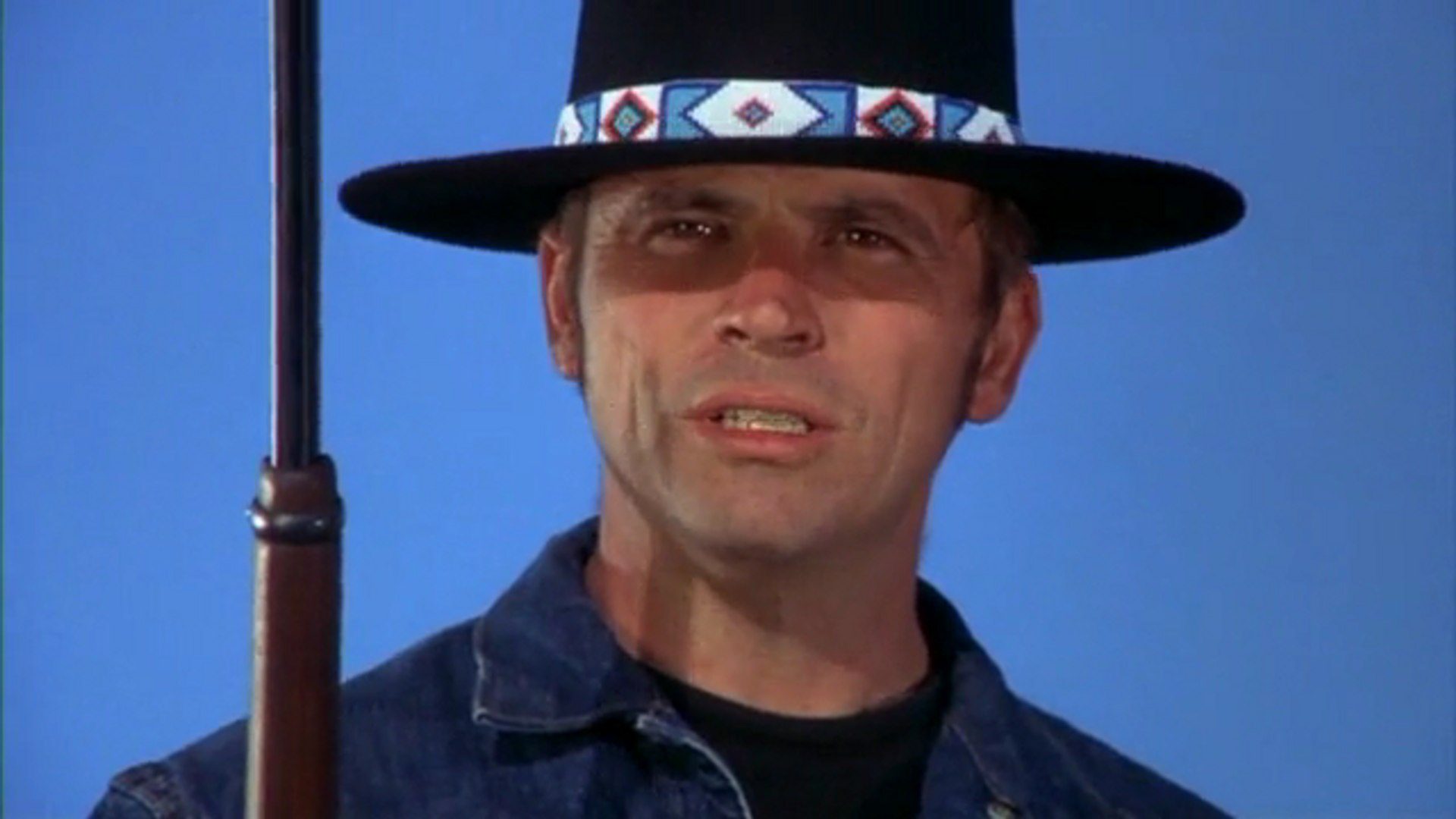

Despondent at the loss of my first hero, my 9-year-old brain went searching for a replacement and found him busy defending the rights of peace-loving Native American kids in Arizona’s high desert.

“Billy Jack” was everything I wanted to be: calm, collected, adored by women, respected by men, and able to do some pretty cool things with his feet. Billy Jack had a knack for showing up just when he was needed, allaying the kids’ fear even as he introduced it into the hearts of their persecutors. Once his work was done, he’d dissolve back into the wilds as mysteriously as he’d appeared.

According to Joseph Campbell, “a hero is any male or female who leaves the world of his or her everyday life to undergo a journey to a special world where challenges and fears are overcome in order to secure a quest, which is then shared with other members of the hero’s community.” In other words, the solitary Billy Jack stands apart from the mainstream, derives his power from forces beyond mortal man’s comprehension, and then shares those powers for the overall good.

In an insecure world filled with insecure people, we are forever looking for our heroes to right the wrongs, to calm our fears, to tell us “everything will be OK.” The conditioning toward this kind of behavior begins, naturally enough, with our parents. They inhabit a world foreign to us as children; the source of their powers is a mystery; their wisdom is beyond reproach; my dad can beat up your dad; my mom is the prettiest on the block; and so on.

As the child’s familiarity with his parents (and their flaws) grows, the parents’ place in the pantheon of heroes is replaced by that of a popular peer, a Hollywood or sports star, etc. We like our heroes, it seems, just not so close that we get a glimpse into their humanness. That’s why it was good Billy Jack kept disappearing back into the forest – nobody wants to see their hero shopping for toilet paper or walking around with food on his chin.

According to Roma Chatterji of the University of Delhi, we see our heroes as symbolic representations of ourselves. Which helps to explain why, at its core, the hero’s journey is seen as a journey within that each of us inevitably must make. Indeed, Campbell used the likes of Jesus, Siddhartha (the Buddha), Moses and Joan of Arc as ultimate examples of the heroic.

But despite the fact all are called to this journey, most refuse. Reasons for denying the call include fear, complacence, laziness, or duty to others (picture the young Luke Skywalker’s yearning to be a Jedi tempered by his Uncle Owen’s reminder of his responsibility to the family farm).

We shouldn’t feel too bad, however. As Campbell pointed out, most heroes initially reject the path until their suffering becomes too great, the call too urgent, the inspiration unmistakable and at last they set out on the journey.

The reward for undertaking the journey is, interestingly enough, the cessation of self. The hero embarks on the journey a mortal/material being and returns a hero, liberated from the physical world he or she has overcome. The hero remains in play only to the degree he or she can be of benefit to others (or until the adoring fans turn hostile and nail him to a tree or burn her at the stake).

There are days I still miss the innocence (ignorance) of my hero worship, when I took comfort in knowing that the Billy Jacks of the world would ride out at the last moment to save wild horses from being turned into dog food. Forty years later I still think the hat is kind of cool too.